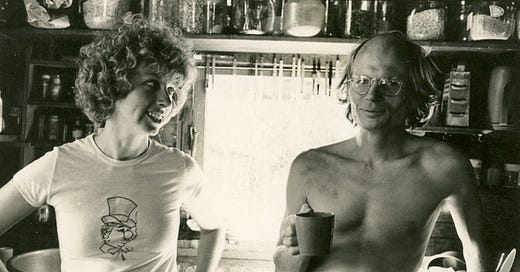

While living in New York and looking for a rural commune to move our family to, my partner and I visited Salmon Creek Farm in 1974. Communes attracted us because we felt it was the best way to raise a family, where the kids would have a bunch of other kids to play and grow with as well as have several adults there to be their communal aunts and uncles— an extended “family of choice.” We believed the nuclear family limited peer and generational interactions for the kids, and put too much pressure on the parents to supply all the modeling for them. We thought the kids would thrive having lots of choices in “siblings” and “parents,” and the adults would have assistance in their childrearing roles.

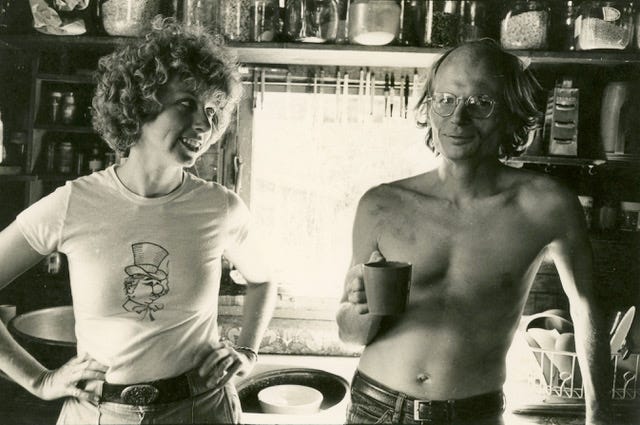

Salmon Creek Farm had the added attraction of having a publishing company there, Freestone Press. My partner and I has been running our Times Change Press in New York City, but then wanted to move us and it to a rural commune. Finding one already with other publishers and writers was an added motivation for us to move across country and to start a new life.

The Mendocino Coast was an ideal location because of its ideal climate— never too hot or too cold, its beautiful wild redwood forests and streamside environment near the coast, and its close proximity to cosmopolitan culture with a strong artists’ community, symphony orchestra, theater company, foreign films series, several rock and world music bands and stimulating progressive political movements to oppose war, nuclear weapons and destruction of our nearby redwood forests, salmon-bearing streams and the environment in general.

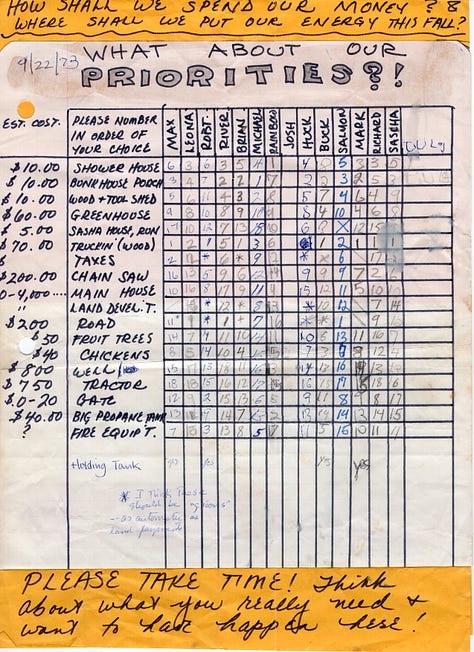

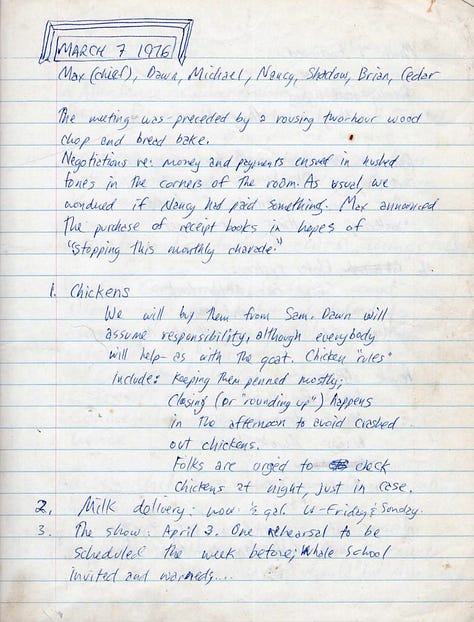

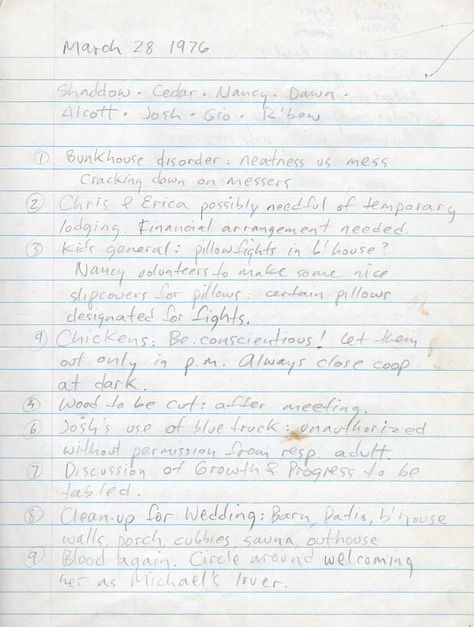

I, personally, found the commune experience very growthful. For me it was a good balance between privacy in our various hillside cabins linked only by foot trails, and community in our shared spaces and in running our commune together. This last came about thru business meetings every Sunday morning where we worked out our group finances and interpersonal conflicts. We had a jointly written set of goals and bylaws, and adults and kids all had an equal right to speak and vote, usually deciding issues consensually. We employed “radical therapy” and “co-counseling” techniques to help us thru the inevitable interpersonal conflicts; they helped us avoid commune self-destruction which was the downfall of many of them in those days. By living closely with a dozen communards and regularly working thru our issues, it greatly helped me learn to how to articulate my feelings, to really “hear” others', and to develop ways to problem solve together.

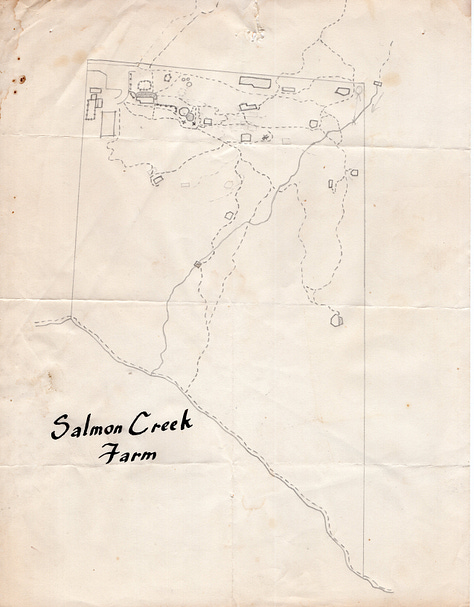

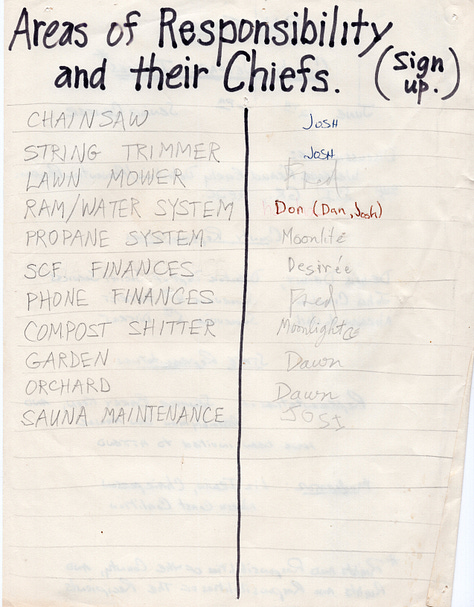

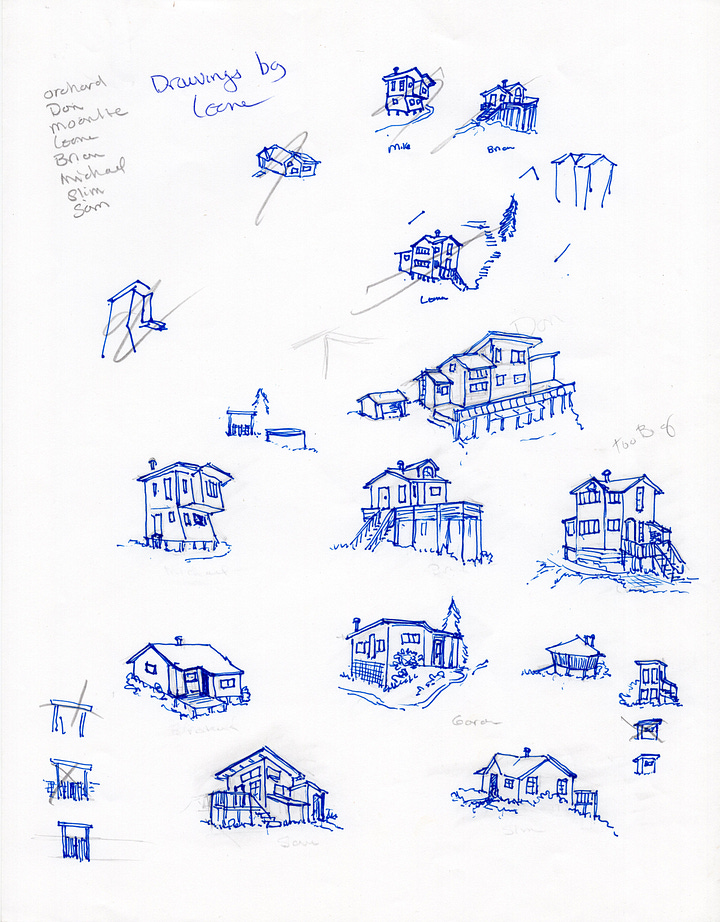

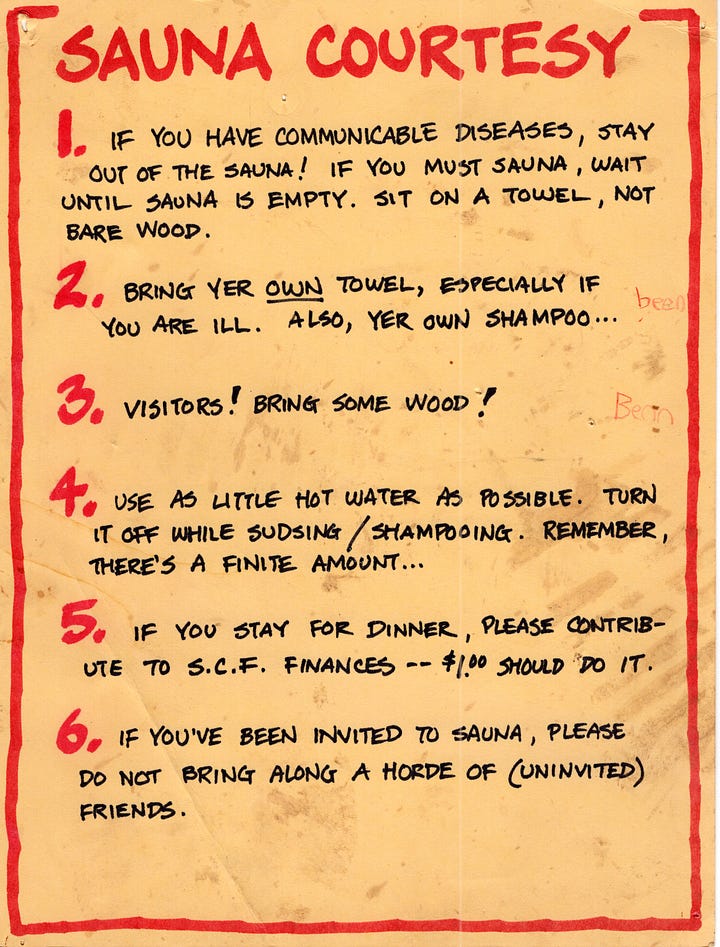

Salmon Creek Farm was structured then as a dozen private cabins which we each designed and built ourselves, and we had a separate central meeting room, kitchen & dining room, garden and orchard we planted, barn for our chickens and goats, and a bathhouse with shower and sauna. Every Sunday we had our weekly meeting in the morning and then a workday in the afternoon, planting fruit trees, repairing fences, barn building or whatever was needed. Sunday evenings we opened the Farm to neighbors and guests for a sauna and supper followed by schmoozing and singing aided by our guitarists and bass player.

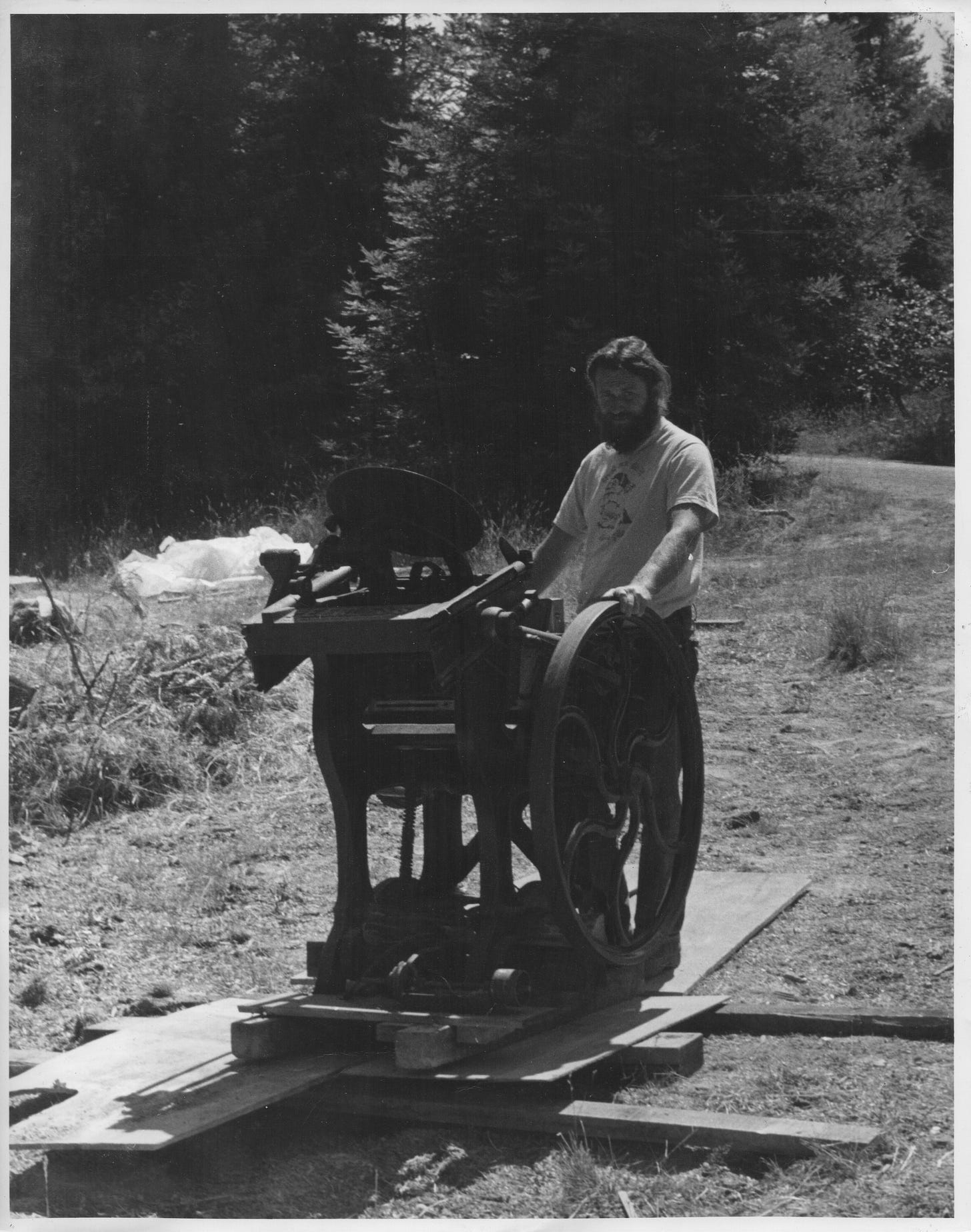

SCF was structured financially with each member, who had to be approved by all existing members, paying around $40 a month to pay for their portion of the land purchase, and another $40/month for communal expenses like groceries, chainsaw repairs, fencing, etc. We each built our own homes and owned them, while all 33 acres of land, from ridge top to Salmon Creek at the bottom, were owned collectively. Each person needed to work off-site to earn the money for this $80/month and their own expenses like car, expenditures in town, travel, etc. But because we lived so simply a couple days of work a week would generally cover our needs. Our first seven years we had no electricity or phones so no bills for that; most clothing came from “free boxes,” thrift stores and neighborhood trading parties; and early on we shared a pickup truck, chainsaws and other necessities of rural living.

Building our simple cabins was not very expensive because we gathered materials, like free siding by taking down abandoned Petaluma chicken coops or scrounging cheap locally-milled lumber and used windows. For example, most of the windows in my bright solar cabin were factory-rejected pinball machine glass tops. They and nearly all of our cabins are still there, fifty years later, housing guests to Salmon Creek Farm today.

Now aged 82, moving to SCF was one of the best choices I made in my life. I lived there 15 years and loved the simple, close-to-earth life with an extended “family of choice,” several of whom I still love and interact with. We, with other area communards and like-minded souls of the then “back-to-the-land,” “simple living” movement helped to form a population and culture rich in political activists, artists of all types and community-serving folk. I live today next-door to SCF, as do a couple other SCF alumni, still interact with it occasionally, and can’t imagine any place else I would rather be. Live simple, share and care about community and the planet. That’s a credo we aimed at then and still sounds good to me today.

by Moonlight (= aka Tom Wodetzki