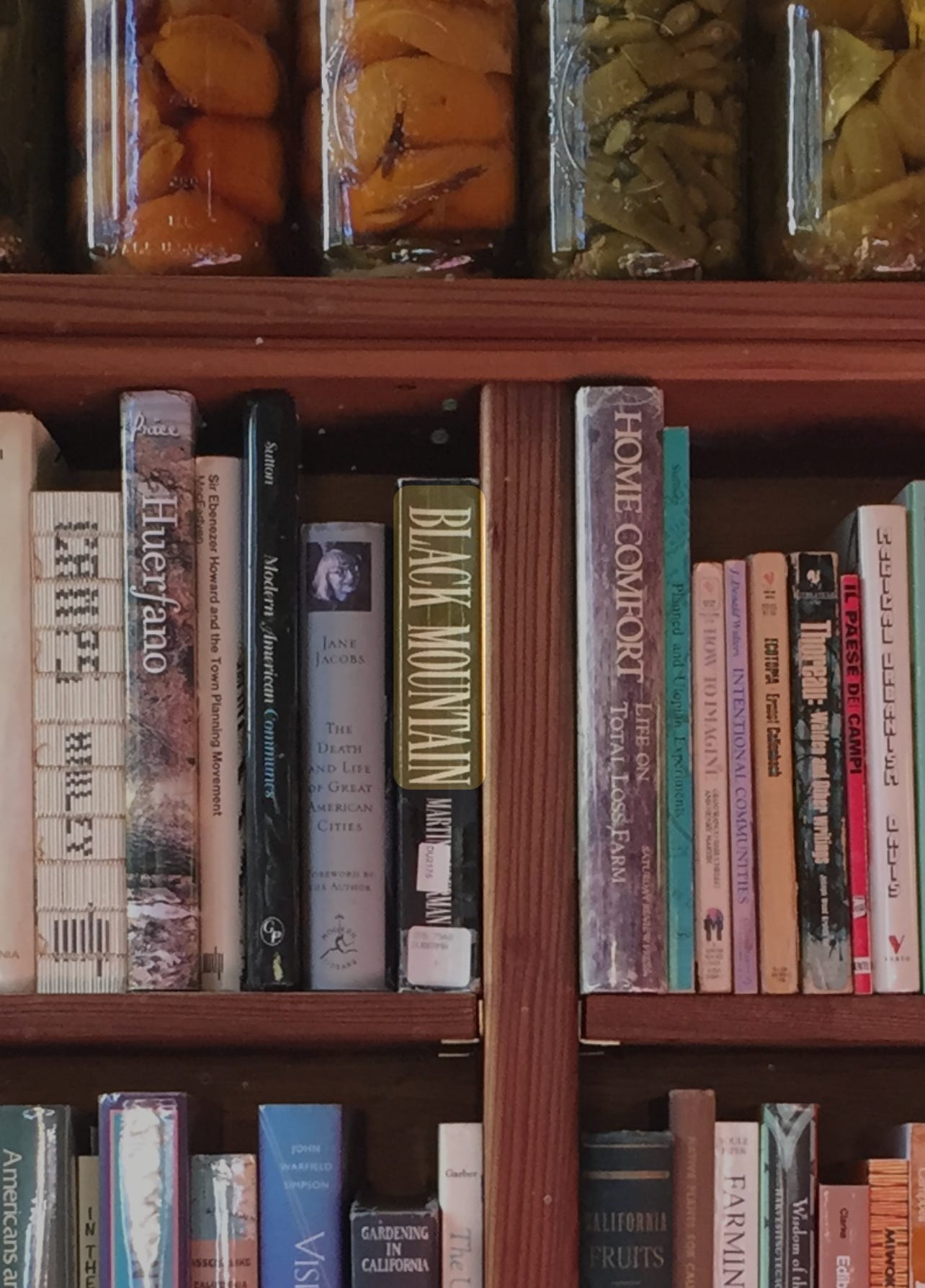

I visited Salmon Creek Farm for two weeks last August, as part of the queer commune that Fritz ran for a handful of months. I feel like I just scratched the surface of understanding what Salmon Creek is really about. When Fritz asked if I'd write for the newsletter, I took the opportunity to dig a little deeper and ask him about some of the ideas that have shaped his vision for the land. Here's an edited and condensed discussion of five books from the SCF Reading List that he considers foundational.

By Gus Wezerek

A Pattern Language: : Towns, Buildings, Construction (1977) by Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein with Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King and Shlomo Angel

Fritz: "Pattern Language" is a very deep exercise in putting together almost like a cookbook for how to create a humane living environment. So it starts out with how to lay out a town, how to lay out the roads, and goes all the way down to how to put chairs around the table and fill your house with personal items. It's a comprehensive, expansive exploration of how to make a space.

There are certain themes that come up again and again. One is nooks, which I'm very interested in. A nook creates a space that is safe and protective and you're enclosed on three sides, but it's open to something else. It's open to a view or a more social environment. People gravitate towards nooks because they're cozy, because they feel safe and protected. But they also allow people to be part of something bigger. It's a metaphor for how to be in the world. How you can find your space or yourself and your own personal needs but still be a part of something bigger and not be isolated.

Gus: There's that nook in Dawn Cabin …

Fritz: We made that one. We dug out the hillside, cut out the wall, used the boards that were on that wall to build the new wall behind and then put a skylight above that.

I love that nook because it's not big enough for someone to properly lay down fully. You have to kind of curl up. What often happens is two people get in there together, and it's a really nice way to be really physically intimate with someone. Like, it really forces you together. I've had a lot of really sweet conversations in that particular nook. And it's where whatever dogs are in the cabin curl up and watch us eat.

Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources (2005) by M. Kat Anderson

Fritz: Anyone who lives in California, anyone who lives anywhere that's been colonized, should read "Tending the Wild." It's a very deep survey into the history of indigenous life with the land in California.

When European colonizers came to California, they saw it as an Eden that was "naturally bountiful." And they perceived the natives who were beneficiaries of the landscape as lazy. What they couldn't see is that the indigenous people were wedded to the land so deeply that their very presence — the daily acts that were passed down over millennia — made the land more beautiful, more productive, more diverse, more healthy.

The book pulls back the curtain on the land that we're on and what should be happening here, and did happen here before it was colonized and industrialized. What the Pomo did, what the indigenous people did, wasn’t farming, wasn't gardening or hunting and gathering. We don't even have a word for it. It's a kind of language that we need to figure out. People are trying to bring it back, but it's a very complicated, nuanced relationship. I think if you spend time at Salmon Creek Farm, you can get a little closer to it.

Cruising Utopia, The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009) by José Esteban Muñoz

Gus: I wanted to ask about "Cruising Utopia."

Fritz: Is that something you'd read before you came to Salmon Creek?

Gus: Yeah, probably six or seven years ago. I remember Muñoz writing about "straight time" — this dogma of linear progress and reproduction and accumulation. And contrasting it with "queer time," which is about creating moments that provide glimpses of utopia.

I thought about "queer time" when I got on the land — how unstructured the days were. We had work days on Saturday. We met for dinner at night. But otherwise, it was really up to us what we did. It was a little bit daunting and it was a little bit freeing.

Fritz: It's the idea of something that's impossible, that you're moving towards that you'll never reach.

Salmon Creek Farm is the land and it's the cabins and it's the redwoods, which are so special, and it's the community of people. But for people who have been here for a certain amount of time, they also know that it's like an idea. It represents an impossibility, because the world is never going to look like this — never going to be this simple, this resourceful and produce so little waste.

It's very aspirational in that way, but it's very rarefied. My vision has always been that Salmon Creek would be a place where people come to surrender to an experience, and then take that back to their lives in some way. What does it feel like to live this close to the land and this close to a community?

It's always a work in progress. You work until the day's over, and then you go to bed, and then you get up and you do more. It's endless and it's incomplete and in that sense it's an ideal.

Parable of the Sower (1993) by Octavia Butler

Fritz: "Parable of the Sower" is such an important book, and it's one I was completely unfamiliar with until someone who was organizing a BIPOC retreat here picked it as a touchstone for their gathering. It's terrifying, the way it's mirroring what's happening right now. It starts near Los Angeles with a young Black woman who’s an empath, feels people's suffering very deeply. She heads north on foot with various people, and finally ends up not in Mendocino, but in Cape Mendocino, which is north of us, on a piece of land where they're going to live close to the land and plants.

"Parable of the Sower" is pretty dark. But it's hopeful, in a way. The book's throughline is understanding that everything is always changing and surrendering to that.

Black Mountain: An Exploration of Community (1972) by Martin Duberman

Fritz: Black Mountain College didn't last long, but it ignited a lot of things in our culture. The students built the houses, they worked the garden, they ran the place, in a way. It was extremely radical. It was a moment of blossoming.

I asked myself: The last 10 years at Salmon Creek Farm, like, what has this place amounted to? What kind of work has emerged? What kind of artists have been here? What have they done? Who have they met? My hope is that it's been 10 years of formation and the best years of this place are still to come.

Gus: I was thinking about that before this conversation. How staying at Salmon Creek was a chance to just exist and take a breath. But the people who were there for the queer summer were artists. There was an application process. So I felt like I was supposed to take the experience and somehow transmute it, to produce something. To take something from Salmon Creek into the wider world and share it. For it not just to be an Instagram post.

This conversation is a transmutation. But if I'm being honest, I feel like I was a failure for not producing something big during my two weeks there. And it seems like you want Salmon Creek to be a place like Black Mountain — a place where people combust, creatively.

Fritz: You can't have a new experience and have it impact you, digest it, while also simultaneously have it inform new work right away. It can take years, even decades. School is like sowing seeds, and they may not take or they may not produce fruit for many years. But a school, hopefully, is like a repository of seeds that's given to each student that they just carry with them the rest of their lives.

The most important work happening that will be inspired by Salmon Creek Farm will not happen here, in the moment. It will happen maybe years or decades later in ways that you can't anticipate. It's not to say that the time here is just empty and disposable, but I do believe in clearing space and seeing what fills it in.